has a zero knowledge

interactive proof. We begin with the graph 3-colorability problem.

has a zero knowledge

interactive proof. We begin with the graph 3-colorability problem.

YALE UNIVERSITY

DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE

| CPSC 461b: Foundations of Cryptography | Notes 19 (rev. 2) | |

| Professor M. J. Fischer | April 2, 2009 | |

Lecture Notes 19

The goal of the next couple of lectures is to show that every language in

has a zero knowledge

interactive proof. We begin with the graph 3-colorability problem.

has a zero knowledge

interactive proof. We begin with the graph 3-colorability problem.

Definition: Let G = (V,E) be a simple graph. A 3-coloring of G is a function ψ : V →{1,2,3}

such that for all (u,v)  E, ψ(u)≠ψ(v).

E, ψ(u)≠ψ(v).

That is, each node is labeled with one of three colors such that no edge connects two nodes of the same color.

Definition: A graph G is 3-colorable if there is a 3-coloring of G. The language G3C is the set of 3-colorable graphs.

Fact G3C is

-complete.

-complete.

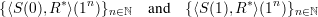

The protocol makes use of a commitment scheme. For now, assume a family of functions

{Cs∣s  {0,1}n}n

{0,1}n}n ℕ, where Cs(σ)

ℕ, where Cs(σ)  {0,1}* for each s

{0,1}* for each s  {0,1}n and σ

{0,1}n and σ  {1,2,3}. Cs(σ) is said to be

the commitment of the sender using coins s to the value σ. Cs(σ) can be computed in polynomial time

given s and σ. We desire that the commitment scheme satisfy two properties:

{1,2,3}. Cs(σ) is said to be

the commitment of the sender using coins s to the value σ. Cs(σ) can be computed in polynomial time

given s and σ. We desire that the commitment scheme satisfy two properties:

Formal properties and construction of more general commitment schemes are given in section 48. The interactive proof for G3C is given in Figure 47.1.

Explanation.

In step 1 of Figure 47.1, the prover randomly permutes the colors in the 3-coloring ψ to

produce a new 3-coloring ϕ of G. It commits to each color ϕ(v) for v  V with the commitment

sequence

V with the commitment

sequence  and sends

and sends  . The verifier checks that ϕ is a 3-coloring by asking the prover to reveal the

colors at the two endpoints of a randomly chosen edge (u,v). The prover does so in step 3. In

step 4, the verifier checks that the colors at u and v were revealed correctly and that they are

different.

. The verifier checks that ϕ is a 3-coloring by asking the prover to reveal the

colors at the two endpoints of a randomly chosen edge (u,v). The prover does so in step 3. In

step 4, the verifier checks that the colors at u and v were revealed correctly and that they are

different.

If both P and V follow this protocol, V always accepts, establishing completeness. If G is not 3-colorable, then any 3-coloring ϕ committed to by a cheating prover P* in step 1 will have at least one edge whose endpoints are colored the same. With probability 1∕|E|, V chooses this edge in step 2. Whatever values P* sends in step 3 will fail V ’s one of V ’s checks, either on correctly opening cu or cv, or it will finds that u and v are colored the same. Hence, V will reject with probability at least 1∕|V |.

The construction of the simulator M* to show that this protocol is zero knowledge is deferred to the next lecture.

A bit-commitment scheme is a pair of probabilistic polynomial-time interactive Turing machines (S,R)

called the sender and receiver, respectively. The common input is a security parameter 1n. The sender’s

private input is a bit v. The sender’s commitment to v is the receiver’s view (r, ) of its interaction with

S, where r is the receiver’s random coins and

) of its interaction with

S, where r is the receiver’s random coins and  is the sequence of messages received from

S.

is the sequence of messages received from

S.

Fix n and let σ  {0,1}. We say a receiver view (r,

{0,1}. We say a receiver view (r, ) is a possible σ-commitment if, for some string

s,

) is a possible σ-commitment if, for some string

s,  describes the messages received by R when R uses local coins r, S uses local coins s, and S has

private input σ. The view is ambiguous if it is both a possible 0-commitment and a possible

1-commitment.

describes the messages received by R when R uses local coins r, S uses local coins s, and S has

private input σ. The view is ambiguous if it is both a possible 0-commitment and a possible

1-commitment.

Here are the requirements for the commit phase of a bit-commitment scheme:

are computationally indistinguishable. The notation ⟨S(v),R*⟩(x) as used here means the random variable describing the receiver’s view in a joint computation of S and R* on common input x, where S has private input v. (Recall the definition of computational indistinguishability in section 26 of lecture notes 10.)

for which the receiver’s view (r,

for which the receiver’s view (r, ) is ambiguous.

) is ambiguous. In the reveal phase, the sender opens the commitment (r, ) by revealing the secret bit v and the

sequence s of local coins that it used during the commit phase. Upon receiving (v,s), the receiver

re-executes the joint computation of the commit phase, simulating S(v) using local coins s,

and simulating R with local coins r. It then checks that the sequence of messages

) by revealing the secret bit v and the

sequence s of local coins that it used during the commit phase. Upon receiving (v,s), the receiver

re-executes the joint computation of the commit phase, simulating S(v) using local coins s,

and simulating R with local coins r. It then checks that the sequence of messages  ′ sent

by S in the simulation matches the sequence

′ sent

by S in the simulation matches the sequence  from the commitment and accepts iff they

agree.

from the commitment and accepts iff they

agree.

Let f : {0,1}*→{0,1}* be a one-way permutation, and let b : {0,1}*→{0,1} be a hard core predicate for f. A commitment scheme is easily derived from f and b.

Unambiguity is immediate since f is a permutation. Hence, if m = (y,τ) for some string y and

τ  {0,1}, then m is a commitment only to the value v = b(s) ⊕ τ, where s = f-1(y) is the unique

inverse of y under f.

{0,1}, then m is a commitment only to the value v = b(s) ⊕ τ, where s = f-1(y) is the unique

inverse of y under f.

Secrecy follows from the fact that b is a hard-core predicate for f. Here’s a sketch of the proof of secrecy.

Suppose some probabilistic polynomial-time algorithm D(m) is able to distinguish commitments to 0 from commitments to 1 with non-negligible probability ϵ(n). Formally

![|P r[D (f(Un),b(Un) ⊕ 1) = 1] - Pr[D (f (Un ),b(Un )) = 1]| ≥ ϵ(n),](ln1922x.png)

where Un is a uniformly distributed random variable over {0,1}n. Without loss of generality, we may assume that the output of D is either 0 or 1, and we may drop the absolute value brackets and assume that

![P r[D (f(Un),b(Un) ⊕ 1) = 1] - Pr[D (f (Un ),b(Un )) = 1] ≥ ϵ(n ).](ln1923x.png)

We construct an algorithm A′ that on input y = f(s) correctly outputs b(s) with non-negligible advantage ϵ′(n) over random guessing. Formally,

![′ 1- ′

P r[A (f (Un )) = b(Un)] ≥ 2 + ϵ(n)](ln1924x.png)

A′(y) chooses τ  {0,1} uniformly at random, constructs m = (y,τ), computes σ = D(m) and outputs

σ ⊕ τ.

{0,1} uniformly at random, constructs m = (y,τ), computes σ = D(m) and outputs

σ ⊕ τ.

From the proof of unambiguity above, m = (y,τ) is a commitment to v = τ ⊕ b(s), where s = f-1(y). Hence, b(s) = τ ⊕ v. Thus, if m is a commitment to v and D(m) outputs v, then A′(y) correctly outputs b(s). Moreover, because τ is chosen at random, m is equally likely to be a commitment to 0 or a commitment to 1.

We leave to the reader the task of showing that A′(f(s)) has an ϵ′(n) advantage at guessing b(s) for some non-negligible function ϵ′(n). This contradicts the assumption that b is hard-core for f. Hence, the assumed distinguisher D does not exist and the commit phase satisfies the secrecy condition.

Although the commitment scheme of section 48.1 is simple, it assumes the existence of one-way permutations. This is a possibly stronger assumption than the existence of one-way functions, for the problem of constructing a one-way permutation assuming only the existence of one-way functions is still open. However, it is known that pseudorandom generators can be constructed assuming only the existence of one-way functions. We now construct a bit-commitment scheme based on a pseudorandom generator, showing that commitment schemes exist if one-way functions exist.

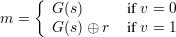

Let G(s) be a pseudorandom generator with expansion factor ℓ(n) = 3n. (See section 29 of lecture notes 12.)

{0,1}3n uniformly at random and sends r to the sender. The sender chooses s

{0,1}3n uniformly at random and sends r to the sender. The sender chooses s  {0,1}n

uniformly at random, computes

{0,1}n

uniformly at random, computes

and sends m to the receiver. The sender’s commitment to v is the receiver view (r,m).

The proof of the secrecy condition is another reducibility argument. Assuming there is a distinguisher between commitments to 0 and commitments to 1, one constructs a distinguisher between G(Un) and U3n, contradicting the assumption that G is a pseudorandom generator. Details are in the textbook.

The proof of unambiguity is more interesting. This commitment scheme does not have perfect unambiguity. For example, if r = 0, then the receiver view (r,G(s)) is a commitment to both 0 and 1. More generally, if there exist s0,s1 such that G(s0) = G(s1) ⊕ r, then the receiver view (r,G(s0)) = (r,G(s1) ⊕ r) is ambiguous. Otherwise, (r,m) is unambiguous for all receiver views (r,m).

Call a value r bad if r = G(s0) ⊕ G(s1) for some s0,s1 and good otherwise. There are

(2n)2 = 22n pairs (s0,s1), where s0,s1  {0,1}n, and each of them gives rise to one bad value

r = G(s0) ⊕ G(s1). All of the other 23n possible values for r are good. Hence, the probability of the

receiver choosing a bad r is exponentially small – only 22n∕23n = 1∕2n, which is a negligible

function.

{0,1}n, and each of them gives rise to one bad value

r = G(s0) ⊕ G(s1). All of the other 23n possible values for r are good. Hence, the probability of the

receiver choosing a bad r is exponentially small – only 22n∕23n = 1∕2n, which is a negligible

function.