Perlis epigram #26: There will always be things we wish to say in our programs that in all known languages can only be said poorly.

We consider rules for the evaluation of expressions in Racket.

1. Constants evaluate to themselves.Constants are expressions like the numbers 18 and -1, the string "hi there!" and the Boolean values #t and #f (for true and false.) As examples of evaluating these expressions in the interaction window in Dr. Racket, we have the following.

> 18 18 > -1 -1 > "hi there!" "hi there!" > #t #t > #f #f(Numbers are actually a fairly complex subject in most programming languages, so for the time being we will consider only integers, that is, positive, negative, and zero whole numbers.)

The term "application" means procedure call. The syntax of an application is as follows.

(proc arg1 ... argn)

where proc is an expression (which evaluates to a procedure),

and arg1, arg2, ..., argn are expressions (which are evaluated to

determine the arguments to the procedure.)

The rule for evaluating an application is the following

2. An application is evaluated by evaluating the first expression (whose value must be a procedure) and each of the rest of the expressions; the procedure is called with the values of the rest of the expressions as its actual arguments; when the procedure returns a value, that value is the value of the application.As an example of an application, we have the following.

> (+ 18 4) 22 >In the application (+ 18 4), + is an identifier which evaluates to a procedure, namely, the built-in procedure to add numbers. The expressions 18 and 4 are constants, which evaluate to themselves according to rule (1). Then the built-in procedure to add numbers is called with the arguments 18 and 4, and returns the value 22, which becomes the value of the whole application expression. Just how + evaluates to a procedure will be seen shortly. As additional examples of applications, we have the following.

> (- 18 4) 14 > (* 6 3) 18 > (quotient 22 6) 3 > (remainder 22 6) 4 >The identifiers -, *, quotient, and remainder evaluate to the built-in procedures to (respectively) subtract, multiply, take the integer quotient, and take the integer remainder. (Using the "division algorithm" we divide 6 into 22 getting a quotient of 3 and a remainder of 4, so 22 = 3*6+4.)

Note that Racket is uncompromising: in an application, the expression for the procedure *always* comes first. What happens when (inevitably) we write something like (18 - 4)? We get an error message, something like:

> (18 - 4) application: not a procedure; expected a procedure that can be applied to arguments given: 18 arguments: ...:

Note exception: (18 . - . 4)The first expression after the left parenthesis is 18, which is a number, not a procedure. The error message comes from the code to evaluate an application and is trying to tell us that it expected a procedure but got 18 instead. Feel free to try things out in the interaction window to see what happens -- it will help you to be able to interpret error messages if/when you see them in response to running your own programs.

The third rule is simple but powerful.

3. The rules apply recursively.This means that sub-expressions are evaluated the same way as any other expressions. As an example, consider the following.

> (+ (* 3 6) 4) 22 >The outer set of parenthesis indicate an application. The first expression is +, which evaluates to the built-in procedure to add numbers. The second expression is (* 3 6), which is another application. We need to find its value to know what the first argument to the addition procedure should be. So (recursively) we evaluate this expression. It is also an application, with first expression *, which evaluates to the built-in procedure to multiply numbers. The other expressions are 3 and 6, which are constants and evaluate to themselves. Then the multiplication procedure is called with arguments 3 and 6 and returns 18. Now we know the value of the first argument to the addition procedure. The expression for the second argument is 4, which is a constant that evaluates to itself. Now we can call the addition procedure with arguments 18 and 4, and it returns 22, which becomes the value of the whole expression.

So what rule can we use to evaluate an identifier like +, *, or remainder? We need the concept of an "environment", which is a table with entries consisting of an identifier and its value. The identifier is said to be "bound" to the value in the environment. There is a top-level environment already defined when you start Dr. Racket; it contains identifiers such as +, *, and remainder, and gives their values as the built-in procedures to add numbers, multiply numbers, and take the remainder of two numbers. We could picture this top-level environment as a table as follows.

identifier | value

--------------------------------

| + | built-in addition procedure

--------------------------------

| * | built-in multiplication procedure

--------------------------------

| remainder | built-in remainder procedure

---------------------------------

(Of course, there are many more than three entries in the

top-level environment.)

Then the rule for evaluating identifiers can be stated as follows.

4. The value of an identifier is found by looking it up in the "relevant" environment.This is well defined up to the specification of the "relevant" environment. For the moment, there is only one environment we will consider, namely, the top-level environment, so that will be the "relevant" one. Returning to the application (+ 18 4), we see that the first expression in the application, the identifier +, is evaluated by looking up its value in the top-level environment, where its value is found to be the built-in addition procedure.

Can we add entries to the top-level environment? Yes, we can do so using the "special form" whose keyword is define. The terminology "special form" means an expression that looks somewhat like an application, but actually has a different evaluation rule. The syntax of define is as follows.

(define identifier expression)

The evaluation rule for this expression is as follows.

5. A define expression adds the identifier to the relevant environment with a value obtained by evaluating the expression.If the identifier is already in the relevant environment, its binding is changed to the value obtained by evaluating the expression. A define expression may look a bit like an assignment statement, but that is the wrong way to think about it. You'll use it in your homework primarily to define procedures in Dr. Racket's definitions window. As an example, if we evaluate the following expression:

> (define age 18) >then the identifier age is added to the top-level environment with the value of the expression 18 (namely 18 itself) as its value. So we can then picture the top-level environment as follows.

identifier | value

--------------------------------

| + | built-in addition procedure

--------------------------------

| * | built-in multiplication procedure

--------------------------------

| remainder | built-in remainder procedure

---------------------------------

| age | 18

---------------------------------

Then we can evaluate age as follows.

> age 18 >And we can proceed to use age in other expressions, for example the following.

> (define new-age (+ age 4)) > new-age 22 >In this case, another identifier, new-age (note that the dash is part of the identifier), is added to the top-level environment, with the value 22, which is the result of evaluating the expression (+ age 4). In detail, + is evaluated by looking it up in the top-level environment, where its value is found to be the built-in addition procedure. The identifier age is also evaluated by looking it up in the top-level environment, where its value is found to be the number 18. The expression 4 evaluates to itself, and the addition procedure is called with the arguments 18 and 4, and returns the value 22. This value is bound to the identifier new-age in the top-level environment, which we can now picture as follows.

identifier | value

--------------------------------

| + | built-in addition procedure

--------------------------------

| * | built-in multiplication procedure

--------------------------------

| remainder | built-in remainder procedure

---------------------------------

| age | 18

---------------------------------

| new-age | 22

---------------------------------

When we evaluate new-age, its value is looked up in the top-level

environment and found to be 22.

Note that when we quit and restart Dr. Racket, the top-level

environment returns to its initial contents, so age and new-age

would no longer be in the top-level environment in that case.

How can we tell a "special form" from an ordinary application expression? They are both enclosed in parentheses, but a "special form" has one of a small number of keywords (eg, define) as the first expression in the list. Note that parentheses in Racket have a rather different function from their use in mathematics, where they can be used for grouping and are sometimes optional. It is important to retrain your intuition so that you do not think of parentheses in Racket as negligible or innocuous.

Try evaluating the expression +, and you will see how Racket represents the built-in procedure +. Try defining * to be + and see what happens. (Remember that you can restore the initial top-level environment by quitting and re-starting Dr. Racket.)

We are programmers! When are we going to define our own procedures? There is a special form with keyword lambda that causes a procedure to be created. The syntax (given incorrectly in the lecture!) is as follows.

(lambda (arg1 ... argn) expression)

The keyword lambda signals that this is a lambda-expression.

The (arg1 ... argn) component is a finite sequence of identifiers

arg1, arg2, and so on, up to argn, that gives names to the "formal

arguments" of the procedure.

The final expression is the "body" of the procedure and indicates

how to compute the value of the procedure from its arguments.

As an example, we can evaluate the following expression.

> (lambda (n) (+ n 4))Evaluating this expression creates a procedure of one formal argument, n, that takes a number, adds 4 to it, and returns the resulting sum. In fact, in this case, the procedure is created, but neither applied nor named, so it just drifts off into the ether. We could not only create it, but also apply it, as follows.

> ((lambda (n) (+ n 4)) 18) 22 >What happened here? The outer parentheses are an application (after the first left parenthesis there is another left parenthesis, not a keyword.) The first expression, (lambda (n) (+ n 4)), is evaluated, which creates a procedure of one argument that adds 4 to its argument and returns the sum. The second expression, 18, is evaluated (to itself), and the procedure that we just created is called on the argument 18. The procedure adds 4 to 18 and returns 22, which is the value of the application. At least the procedure got applied in this case, but only once, and then it drifted off into the ether. To use a procedure multiple times, we can give it a name, eg, by using the define special form. We'll see more details of procedures, and more examples, in the next lecture.

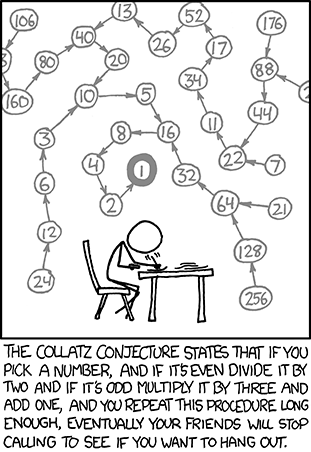

Want to win a Fields Medal? Solve the

Collatz Conjecture! (aka, Kakutani's Problem).

Want to win a Fields Medal? Solve the

Collatz Conjecture! (aka, Kakutani's Problem).

We define a function (collatz n) (where n is an arbitrary positive integer) which behaves as follows:

Next, let's define a sequence of Collatz numbers, such the output of each call becomes the input of the next, unless and until you arrive at 1. The conjecture part is to prove that this series will always converge to 1.

We now turn to some Racket code that implements Collatz 0119.rkt (Note use of trace and untrace)