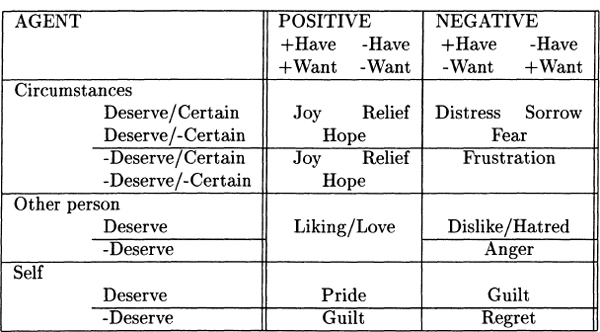

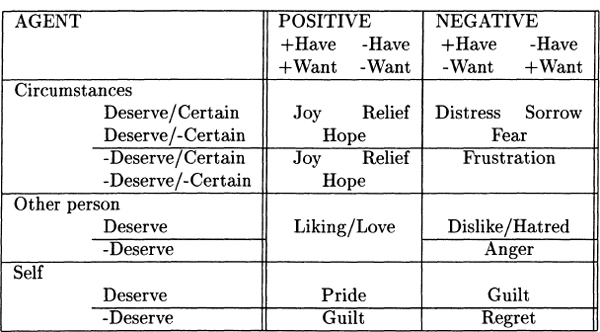

The cognitive dimension of affect has been explored by Roseman (1982), who developed a goal-based taxonomy of emotion. Table 4.3 illustrates Roseman’s basic set of emotions.

This taxonomy uses the following dimensions.

Agent. The entity responsible for the goal state. The agent could be indefinite (circumstances in the world), another person, or the agent experiencing the emotion.

Goal State. This can be either positive or negative. A positive goal state exists when an agent achieves a desired goal (+Have +Want), or avoids an undesired goal (-Have -Want). A negative goal state exists when the agent achieves an undesired goal (+Have -Want) or fails to achieve a desired goal (-Have +Want).

Deservedness. This dimension reflects whether or not the agent deserved to achieve or fail to achieve the goal state.

Certainty. The agent may or may not know the outcome of a goal state. That is, if the emotion involves a future event, or an event that has taken place but whose outcome is not known by the agent, then that goal state is uncertain.

| AGENT | POSITIVE | NEGATIVE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| +Have | -Have | +Have | -Have | ||

| +Want | -Want | -Want | +Want | ||

%%latex \begin{center} \begin{tabular}{|c|c|c| } \hline cell1 & cell2 & cell3 \\ \end{tabular} \end{center}

Dyer incorporated this theory in his BORIS program [Dyer, 1982] to make inferences about affect. Here are some examples of goal-based affective inferences.

If agent X achieves a desired goal, then X is happy.

If agent Y thwarts a desired goal of agent X, then X is angry with Y.

If agent X avoids an expected negative outcome, then X is relieved.

This approach permits inference of goal states based on affect, and vice versa.

Example 4.56 John was a candidate for mayor. When the results came in election night, he was ecstatic.

Example 4.57 Mary was a candidate for mayor. She lost the election.

In the first story, we can infer the result (victory), given the emotional response. In the second story, we can infer the emotion (disappointment), given the result.

It should be clear that this type of inference is compatible with the goal hierarchy model given earlier. In addition, the concept of importance can be tied into the model of affect as follows.

Principle 7 The importance of a goal is proportional to the degree of affective response to the status of that goal.

For example, the difference among happiness, joy, and ecstasy relates to the importance of the goal that is achieved or anticipated. Thus, importance translates into ardor or passion, while apathy or velleity is devoid of emotion.

Happiness does not depend only on the world, but also on one’s idiosyncratic goal hierarchy. Two people in the same situation may have different, even opposite, affects.

It is also common for the same person to experience different emotions at the same time. We speak of someone having “mixed feelings” or “mixed emotions” over some situation. This phenomenon reflects the fact that a given event may affect many different goals of the same person, both positively and negatively.

Consider these two stories.

Example 4.58 John tore his t-shirt when his team won the championship.

Example 4.59 Mary’s new make-up made her nauseated.

In each case, there is a conflicting goal state. In the first case, John wanted his team to win, and did not want to tear his shirt. In the second case, Mary wanted to use her new make-up, but did not want to have it make her sick. We assume that John is not upset about his shirt, and that Mary will probably stop using the make-up. John is happy, and Mary is frustrated. We can infer a regnant emotion based on the relative priorities of the goal states. The next two cases are more complex.

Example 4.60 John broke his arm when his team won the championship.

Example 4.61 Mary’s new medication made her nauseated.

In cases like these, there is no single regnant emotion. From our model, we would predict that John and Mary might each have a significant goal conflict. As the relative importance of the conflicting goal states becomes closer, it is harder to decide between them. In the first case, John really has no pending action. He cannot now prevent his broken arm or lose the championship. There is nothing further for him to do except to decide how he feels. In the second example, Mary is faced with a choice. Her decision and her affective response will reflect the relative importance of the underlying goals.