YALE UNIVERSITY

DEPARTMENT OF COMPUTER SCIENCE

| CPSC 467a: Cryptography and Computer Security | Notes 13 (rev. 1) | |

| Professor M. J. Fischer | October 19, 2006 | |

Lecture Notes 13

The Jacobi symbol extends the Legendre symbol to the case where the “denominator” is an arbitrary odd positive number n.

Let n be an odd positive integer with prime factorization ∏ i=1kpiei. We define the Jacobi symbol by

| (1) |

where the symbol on the left is the Jacobi symbol, and the symbol on the right is the Legendre symbol. (By

convention, this product is 1 when k = 0, so  = 1.) Clearly, when n = p is an odd prime, the Jacobi

symbol and Legendre symbols agree, so the Jacobi symbol is a true extension of our earlier

notion.

= 1.) Clearly, when n = p is an odd prime, the Jacobi

symbol and Legendre symbols agree, so the Jacobi symbol is a true extension of our earlier

notion.

What does the Jacobi symbol mean when n is not prime? If  = -1 then a is definitely not a

quadratic residue modulo n, but if

= -1 then a is definitely not a

quadratic residue modulo n, but if  = 1, a might or might not be a quadratic residue. Consider the

important case of n = pq for p, q distinct odd primes. Then

= 1, a might or might not be a quadratic residue. Consider the

important case of n = pq for p, q distinct odd primes. Then

so there are two cases that result in  = 1: either

= 1: either  =

=  = +1 or

= +1 or  =

=  = -1. In the

first case, a is a quadratic residue modulo both p and q, so a is a quadratic residue modulo n. In the second

case, a is not a quadratic residue modulo either p or q, so it is not a quadratic residue modulo n, either.

Such numbers a are sometimes called “pseudo-squares” since they have Jacobi symbol 1 but are not

quadratic residues.

= -1. In the

first case, a is a quadratic residue modulo both p and q, so a is a quadratic residue modulo n. In the second

case, a is not a quadratic residue modulo either p or q, so it is not a quadratic residue modulo n, either.

Such numbers a are sometimes called “pseudo-squares” since they have Jacobi symbol 1 but are not

quadratic residues.

The Jacobi symbol is easily computed if the factorization of n is known using Equation 1 above and

Theorem 1 of lecture 12, section 67. Similarly, gcd(u,v) is easily computed given the factorizations of u

and v, without resort to the Euclidean algorithm. The remarkable fact about the Euclidean algorithm is that

it lets us compute gcd(u,v) efficiently even without knowing the factors of u and v. A similar algorithm

allows the Jacobi symbol  to be computed efficiently without knowing the factorization of a or

n.

to be computed efficiently without knowing the factorization of a or

n.

The algorithm is based on identities satisfied by the Jacobi symbol:

= 1;

= 1;  = 0 for n

= 0 for n 1;

1;

= 1 if n ≡±1 (mod 8);

= 1 if n ≡±1 (mod 8);  = -1 if n ≡±3 (mod 8);

= -1 if n ≡±3 (mod 8);

=

=  if a1 ≡ a2 (mod n);

if a1 ≡ a2 (mod n);

=

=

;

;

= -

= - if a ≡ n ≡ 3 (mod 4).

if a ≡ n ≡ 3 (mod 4).

=

=  if a ≡ 1 (mod 4) or (a ≡ 3 (mod 4) and n ≡ 1 (mod 4));

if a ≡ 1 (mod 4) or (a ≡ 3 (mod 4) and n ≡ 1 (mod 4));

There are many ways to turn these identities into an algorithm. Below is a straightforward recursive approach. Slightly more efficient iterative implementations are also possible.

int jacobi(int a, int n)

/⋆ Precondition: a, n >= 0; n is odd ⋆/ { if (a == 0) /⋆ identity 1 ⋆/ return (n==1) ? 1 : 0; if (a == 2) { /⋆ identity 2 ⋆/ switch (n%8) { case 1: case 7: return 1; case 3: case 5: return -1; } } if ( a >= n ) /⋆ identity 3 ⋆/ return jacobi(a%n, n); if (a%2 == 0) /⋆ identity 4 ⋆/ return jacobi(2,n)⋆jacobi(a/2, n); /⋆ a is odd ⋆/ /⋆ identities 5 and 6 ⋆/ return (a%4 == 3 && n%4 == 3) ? -jacobi(n,a) : jacobi(n,a); } |

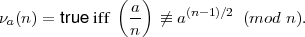

Recall that a test of compositeness for n is a set of predicates {τa(n)}a Z*n such that if τ(n) succeeds (is

true), then n is composite. The Solovay-Strassen Test is the set of predicates {νa(n)}a

Z*n such that if τ(n) succeeds (is

true), then n is composite. The Solovay-Strassen Test is the set of predicates {νa(n)}a Z*n,

where

Z*n,

where

If n is prime, the test always fails by Theorem 1 of lecture 12, section 67. Equivalently, if some νa(n) succeeds, then n must be composite. Hence, the test is a valid- test of compositeness.

Let b = a(n-1)∕2, so b2 ≡ an-1. There are two possible reasons why the test might succeed. One possibility

is that an-1 ⁄≡ 1 (mod n) in which case b ⁄≡±1 (mod n). This is just the Fermat test ζa(n) from

section 51 of lecture notes 10. A second possibility is that an-1 ≡ 1 (mod n) but nevertheless, b ⁄≡ (mod n). In this case, b is a square root of 1 (mod n), but it might have the opposite sign from

(mod n). In this case, b is a square root of 1 (mod n), but it might have the opposite sign from  , or it

might not even be ±1 since 1 has additional square roots when n is composite. Strassen and Solovay show

that at the probability that νa(n) succeeds for a randomly-chosen a

, or it

might not even be ±1 since 1 has additional square roots when n is composite. Strassen and Solovay show

that at the probability that νa(n) succeeds for a randomly-chosen a  Z*n is at least 1∕2 when n is

composite.1

Z*n is at least 1∕2 when n is

composite.1

The Miller-Rabin Test is more complicated to describe than the Solovay-Strassen Test, but the probability of error (that is, the probability that it fails when n is composite) seems to be lower than for Solovay-Strassen, so that the same degree of confidence can be achieved using fewer iterations of the test. This makes it faster when incorporated into a primality-testing algorithm. It is also closely related to the algorithm presented in section 55.3 (lecture notes 10) for factoring an RSA modulus given the encryption and decryption keys.

The test μa(n) is based on computing a sequence b0,b1,…,bk of integers in Z*n. If n is prime, this sequence ends in 1, and the last non-1 element, if any, is n- 1 (≡-1 (mod n)). If the observed sequence is not of this form, then n is composite, and the Miller-Rabin Test succeeds. Otherwise, the test fails.

The sequence is computed as follows:

An easy inductive proof shows that bi = a2im mod n for all i, 0 ≤ i ≤ k. In particular, bk ≡ a2km = an-1 (mod n).

To see that the test is valid, we must show that μa(p) fails for all a  Z*p when p is prime. By Euler’s

theorem2 ,

ap-1 ≡ 1 (mod p), so we see that bk = 1. Since 1 has only two square roots, 1 and -1, modulo p, and

bi-1 is a square root of bi modulo p, the last non-1 element in the sequence (if any) must be -1 mod p.

This is exactly the condition for which the Miller-Rabin test fails. Hence, it fails whenever n is prime, so if

it succeeds, n is indeed composite.

Z*p when p is prime. By Euler’s

theorem2 ,

ap-1 ≡ 1 (mod p), so we see that bk = 1. Since 1 has only two square roots, 1 and -1, modulo p, and

bi-1 is a square root of bi modulo p, the last non-1 element in the sequence (if any) must be -1 mod p.

This is exactly the condition for which the Miller-Rabin test fails. Hence, it fails whenever n is prime, so if

it succeeds, n is indeed composite.

How likely is it to succeed when n is composite? It succeeds whenever an-1 ⁄≡ 1 (mod n), so it succeeds whenever the Fermat test ζa(n) would succeed. (See section 51 of lecture notes 10.) But even when an-1 ≡ 1 (mod n) and the Fermat test fails, the Miller-Rabin test will succeed if the last non-1 element in the sequence of b’s is one of the square roots of 1 other than ±1. It can be proved that μa(n) succeeds for at least 3∕4 of the possible values of a. Empirically, the test almost always succeeds when n is composite, and one has to work to find a such that μa(n) fails.

For example, take n = 561 = 3 ⋅ 11 ⋅ 17. This number is interesting because it is the first Carmichael

number. A Carmichael number is an odd composite number n that satisfies an-1 ≡ 1 (mod n) for all

a  Z*n. (See http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CarmichaelNumber.html.) These are the

numbers that I have been calling “pseudoprimes”. Let’s go through the steps of computing

μ37(561).

Z*n. (See http://mathworld.wolfram.com/CarmichaelNumber.html.) These are the

numbers that I have been calling “pseudoprimes”. Let’s go through the steps of computing

μ37(561).

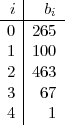

We begin by finding m and k. 561 in binary is 1000110001 (a palindrome!). Then n - 1 = 560 = (1000110000)2, so k = 4 and m = (100011)2 = 35. We compute b0 = am = 3735 mod 561 = 265 with the help of the computer. We now compute the sequence of b’s, also with the help of the computer. The results are shown in the table below:

This sequence ends in 1, but the last non-1 element b3 ⁄≡-1 (mod 561), so the test μ37(561) succeeds. In

fact, the test succeeds for every a  Z*561 except for a = 1,103,256,460,511. For each of those values,

b0 = am ≡ 1 (mod 561).

Z*561 except for a = 1,103,256,460,511. For each of those values,

b0 = am ≡ 1 (mod 561).

In practice, one only wants to compute as many of the b’s as necessary to determine whether or not the test succeeds. In particular, one can stop after computing bi if bi ≡±1 (mod n). If bi ≡-1 (mod n) and i < k, the test fails. If bi ≡ 1 (mod n) and i ≥ 1, the test succeeds. This is because we know in this case that bi-1 ⁄≡-1 (mod n), for if it were, the algorithm would have stopped after computing bi-1.